A Sommelier's wine secrets

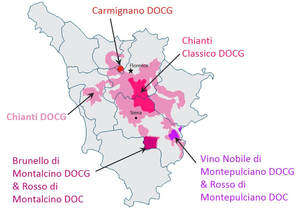

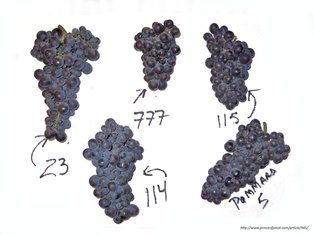

Menu

A sturdy and bold Chianti loaded with opulent flavors of dark cherry, plum, tobacco, walnut skin and licorice. The tannins are grippy, yet smooth and the pronounced acids make this the perfect accompaniment to a variety of hearty Italian dishes. This wine can be purchased at WTSO.com for $15.  2015 Vitanza Italian Red Blend IGT - Exotic and intriguing flavors of plum and dark cherry dominate the palate, while notes of almond, black leather, sweet tobacco and licorice percolate through. On the long finish, you'll experience bold, sturdy tannins and crisp acids. This is great by for $10 on WTSO website.  Dr. Heidemanns-Bergweiler 2018 Riesling Auslese Bernkasteler Badstube - Bright, zesty lemon and grapefruit flavors accompany notes of nectarine, orange blossom, freesia and chamomile. The finish is off-dry but the acids accentuate the fruit flavors and carry them through to the finish. This is an excellent wine to pair with spicy dishes. This Riesling costs around $10 at Total Wine.  I’ve come to the conclusion that the ancient Greeks were both thinkers and drinkers. It wasn’t until a near trademark infringement situation that I realized the Greeks had a plethora of vessels for wine. The Athena (mother) of all wine carrying vessels was the amphora, a large two handled carboy used in shipping large quantities of wine. Next, and slightly smaller, was the crater, a large bowl used to mix the wine with water before drinking. What’s up with that? The kylix, a gallon size wine jug, was used for transporting wine from the crater to the oinochoe, a one handed pitcher. Finally, the smallest of all wine vessels was the cantharos, a two handled cup for drinking the wine. This leads me to think that there was a vast amount of wine being made, transferred and consumed by the Greeks during this particular era in history. However, I also think that the Greeks were more concerned about quantity than quality, which may say something about Greek wine today. My feeling is that if the ancient Greeks even thought about quality, it was probably only after drinking it in quantity.  Chianti, Chianti Classico and Super-Tuscan wines are all produced from the same varietal of grape, Sangiovese, which is grown in the Tuscany region of Italy. During the twentieth century, the Chianti producers focused on capturing market share and not producing quality wine, thus tarnishing the Chianti name. Chianti became associated with low prices and low levels of quality; the cheap and cheerful, light red Italian wine in a straw-covered bottle. In an attempt to recapture the Chianti image of quality, wines from the region of Chianti Classico soon became the new focus. What sets Chianti Classico apart, is that it is a small specific area within the greater Chianti region possessing slightly different soils, climate and wine production methods. Decades later, another attempt to recapture the Chianti image of quality was the creation of the Super-Tuscans. This was another marketing tool to increase the prestige and price of the simpler and less expensive Chianti and Chianti Classico wines. Super-Tuscans are made from the same Sangiovese grape; however, they are blended with Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot instead of the old world Trebbiano or Malvasia Biance grapes. It turns out that a few twists on an old grape can squeeze a little more green stuff out of it.  I recently participated in a barrel tasting and noted something that was quite interesting All of the barrels contained wine made from Pinot noir grapes grown at the same vineyard site, cared for in the same manner and produced by the same winemaker, yet they had strikingly different characteristics. The only difference was the type of Pinot noir vine that produced the grapes. Pinot noir has a tendency to mutate easily, and over the years, subtle deviations from the original have demonstrated qualities that winemakers wanted to capture. The specific mutations have been duplicated by grafting, resulting in vines that are identical to each other (clones), yet subtly different from other Pinot noir vines, just the same as a violin, cello and viola are related and similar, yet not exactly the same. Winemakers and vineyards use these differences to their advantage and select specific clones to suit their tastes and environment. So when you get a bottle of Pinot noir, the wine may be produced from one single clone or a combination of several clones depending on the intention of the winemaker. What are the differences between these clones? There has been much discussion and speculation among winemakers and drinkers about the characteristics and attributes of certain clones. I’ve compiled a few notable characteristics of each clone, all of which are cultivated in Oregon.

Wädenswil Clone – This is the work horse of all the clones. It was cultivated for its reliability and heartiness. The grapes that come from these clones possess crisp acids, red fruit and a simple straight forward structure. The Teen Clones – Besides the fact that they tend to ignore the advice of their parent clones, these clones usually possess red fruit aromas and flavors and are lighter and brighter than the 667 or 777 clones. Clone #113 – The most elegant of the “teen” clones with prominent floral components, terrific texture and moderate tannins. Clone #114 – This particular clone also has rich aromas and good structure, but is primarily cultivated for its darker color and stronger tannins. Clone #115 – This is known as the “quality producer” since it possesses a deep purplish color, spicy aromas and notable long tannins which enable the wine to age. This particular clone can make a great wine on its own. The Sixes and Sevens- These clones produce darker and fleshier wines with flavors of black fruit. Clone #667 – This clone is known for its intense color, aromas, black sweet fruit and fine tannins. Clone #777 – Higher in quality and consistency than the other clones, 777 possesses denser and more complex notes of earth, black fruit, cassis, leather and tobacco. Pommard – Named for the famous region of Burgundy, this clone is known for its blue-black fruit, superior balance, complexity and intense color. It yields a more viscous wine with a richer mouth feel. So the next time you taste a glass of Pinot noir, chances are that you are enjoying the blending of an orchestral section more so than experiencing an individual instrument.  If my kids needed a quick buck, I would give them a dollar for every 1st growth Bordeaux Château they can name; Lafite-Rothschild, Latour, Margaux, Haut-Brion and Mouton-Rothschild. Why? Well, the Sommelier in me hopes that one day they might have the opportunity to try one of these aristocratic wines and I wouldn’t want them to miss out because they couldn’t identify them. Plus, I would insist that they bring me, their one and only mother, a bottle of any 1st growth they taste. The odds are that they, like us, are more likely to consume one of the other 56 Châteaux (2nd-5th growths) or petit château wines simply because there are more of them and they’re more accessible. Some of these “Cru Bourgeois” wines are still pretty amazing. Before you can truly appreciate the crème de la crème, you need to drink some $19.99 (or less) Bordeaux wines. It’s kind of like the theory of the frog prince(ss). You’ve got to kiss a lot of frogs before you can appreciate it when you find the prince(ss). As far as my kids, I know their future will include lots of frogs and mediocre wines, but if I can do one little thing to prepare them to have their eyes (or mouths) open to recognize a prince(ss) or 1st Growth, it’s worth a buck.  Just a few decades ago, if you asked any wine expert to name the preeminent winemaking regions of Tuscany, they would place Chianti Classico and the surrounding sub-zone of Chianti at the top of the list. This latter expanse includes the prestigious hilltop towns of Montalcino, birthplace of the Brunello grape and Montepulciano, producer of the renowned Vino Nobile. Along the Tuscan Coastline, a mere 60 miles away, lies the remote winemaking area of Maremma. Most people had never heard of Maremma, but it was no secret to the local winemakers who knew its potential for producing quality Sangiovese. Eventually, this remote, obscure area would catch the attention of winemakers worldwide and turn the winemaking world on its ear. The hospitable climate and limestone-rich soils not only provided the right ingredients to grow Sangiovese, but what really made this area stand out was its ability to produce complex and expressive foreign varietals like Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah. The wines made from these foreign varietals were so phenomenal that the Italian winemakers forfeited their prized DOC and DOCG quality status to blend them into their Sangiovese wines. This earthshaking, revolutionary act in Italian winemaking marked the birth of the ‘Super Tuscan’ wine and Maremma was the epicenter. Antinori’s Sassicaia is one of the most celebrated wines from this region, helping to pave the way for a succession of these stylish wines over time. While Sangiovese wines from Chianti and Chianti Classico have established reputations, there are still unknown treasures yet to be discovered in the nearby hills of Maremma.

|

Annette Solomon, CS

CategoriesArchives

December 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed